«Italy, 2nd June 1946: The Birth of a Republic»

By Luciano Casali and Roberta Mira. Bolonia University – Italy

On 2nd June 1946, Italians were called to choose the form of State that Italy should have after the end of Second World War. The institutional referendum opposed republic, something new for the Italian state, and monarchy, which had governed since 1861, when the Italian Peninsula was unified under the power of the Royal House: the Savoy.

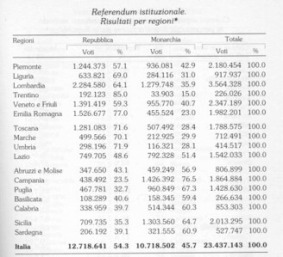

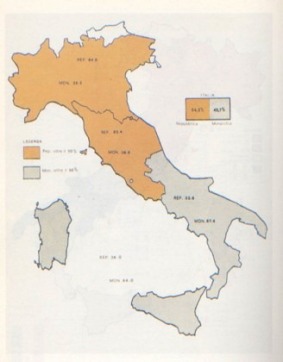

More of the 89% of citizens voted, women included (after the Second World War they gained the right to vote), and the referendum resulted in the victory of the republic with 12,718,614 votes (54.3%) for it and 10,718,502 (45.7%) for monarchy.

In order to understand how that result was achieved, we need to have a quick look at the previous Italian history, focusing on the period that goes between 1943 and 1946.

Italy, which participated in June 1940 in the Second World War with Nazi Germany and which was guided by Benito Mussolini, fascism’s Duce, was governed in October 1922 by King Victor Emanuel III.

Although the fascist regime entirely changed the Albertine Statute (named after King Charles Albert, it was the Italian Constitution in force from 4th March 1848) to obtain a strong supremacy on other State’s powers in order to build a dictatorship, it didn’t erase the monarchy. Being it that way, the king still was the Head of State. When the conflict started to go against Germany and its allies’ interests, Victor Emanuel III, who had always supported fascism and its military conquests (which had gave him the Emperor title), tried to dissociate Italy from the fascist regime.

On 25th July 1943, taking advantage of the Grand Council of Fascism’s sentence against Mussolini to carry out his duty guaranteed by the Albertine Statute, the king gave the order to arrest the Duce and put in his place the government’s guide General Badoglio.

During the next months, the monarchy got in touch with Great Britain and the United States, as their military forces occupied Sicily since July 1943, to ask for a separated truce. Negotiations finally resulted in the armistice of 3rd September, although Italians just knew about it on 8th September.

The armistice caused Germany’s reaction, although it was ready long time ago to Italy’s abandonment before the conflict. The Germans military occupied a part of the south of the country and practically all the center and north, and they took a great number of soldiers from the Italian army, who didn’t have by that time any kind of orders from the king or Badoglio (they finally ran away from Rome to the south, with the Anglo-American army). The Germans freed Mussolini and gave him the chance of creating a new fascist government, the Italian Social Republic, with jurisdiction over the center and north of the country.

Until the spring of 1945, Italy lived in a situation of administrative and politic division, with a center-north in which governed the Nazis and the Italian Social Republic, and a center-south in hands of the monarchy and under control of the allied powers. While in the center-north there were fights against the Nazi and fascist forces, the Partisan Movement of Italy was created and the war continued until 1945, in the center-south, where all the territories were free and out of the conflict, the antifascist partisans and the Italian government started in 1944 the transition from fascism to a new free Italy. Leaving apart, for reasons of space, the Italian Resistenza and its movements (even though they are vital for the post-war period development of Italian history), we go into details of the situation of the freed Italian territory in order to follow the steps that led to the referendum on 2nd June 1946.

After the armistice, the institutional issue was very complicated for antifascist political parties, as they had to recover their figure after the fall of fascism and their position towards the south of Italy, the allies and their fight against fascists and Nazis. The Socialist Party, the Action Party, the Communist Party, the Liberal Party, the Christian Democracy Party and the Labour Democratic Party, which represented the National Liberation Committee, didn’t agree on the projects of the future Italy to build. Basically, two parts were confronted: on the one hand, communists, actionists and socialists pointed to a deep renovation of political, social and economic structures of the country; on the other hand, the rest of the political parties proposed a more moderated or clearly conservative position. Despite those differences, the representatives of the National Liberation Committee demanded the abdication of the king and the creation of a government that expressed antifascism. Regarding the form of the state, political representatives were willing to wait until the end of the war and initiate a popular referendum in order to get the last decision, but at the same time, they weren’t willing to maintain the government with Victor Emanuel III. Given that Great Britain and the United States supported General Badoglio and the monarchy, we can see that Italy found itself on a dead end.

During the months of March and April 1944, a succession of factors completely cleared the situation. General Badoglio’s government got the official recognition of the Soviet Union, desiring not to leave the decision in hands of the United States and Great Britain. This recognition was followed by a memorandum of the Soviet Foreign Minister, who highlighted the importance of a cooperation between the Italian government and the antifascist parties for the sake of the struggles against Nazis. And also, by doing this he forced Great Britain and the United States to open to Italian antifascists.

The Italian communist leader Palmiro Togliatti, who was coming back from Moscow, marked a turning point in the politics of the Italian Communist Party and the antifascist formation. Communists considered the compromise with other parties in the fight against Nazi occupation and fascism very important, and they agreed to support the monarchy and the south’s government until the final victory, and they postponed the solution of the institutional issue of the country. Finally, the king gave in to pressures of some liberal characters and of the Anglo-Americans in order to find a compromise in which abdication, rejected by Victor Emanuel III, wasn’t planed. So, the king abdicated in exchange of appointing his son Umberto as Lieutenant General of the Realm after Rome was taken by the allies powers and retiring to his private life.

Before such events, by the end of 1944, a government of national antifascist unity was created and, for the first time since the overthrow of Mussolini, could see the participation of all the exponents of antifascist parties. The Head of State still was General Pietro Badoglio, supported by British and Americans as a guarantee of the armistice. But the institutional issue wouldn’t be brought up until the end of the conflict, with the approval of the National Liberation Committee and the Liberation Committee of Milan, where the headquarters of the Partisan Movement in the center-north of Italy were found.

A first solution of the problem came with the Legislative Decree of the Lieutenant of the Realm no. 151 of 25th June 1944, started by the government that took charge after Rome’s liberation, still formed by antifascist parties. However, this time they weren’t guided by General Badoglio but by the moderated Ivanoe Bonomi, representative of Italian prefascist parties and, up until then, president of the National Liberation Committee. According to the legislative decree, by the end of the war the Italian people should choose the institutional form, not through a direct referendum in which the people could be for monarchy of republic, but through a Constituent Assembly that would gather by the middle of 1946 and should write the new Italian Constitution and choose the state’s form.

The referendum’s idea was clearly supported by Lieutenant Humbert of Savoy, the Anglo-Americans, the Liberal Party and the Christian Democracy Party. They feared that a Constituent Assembly chosen after Second World War could taka a strongly republican connotation caused by the presence of left-winged parties (communists, socialists and the Action Party). Those who supported a popular referendum and a postponement of elections didn’t all have in mind saving the monarchy, but they were all worried because of the progressive character that a left-winged Constituent Assembly could give to the new Italian state. By postponing the first political elections of Italian post-war period, anxieties of renovation and tension atmosphere after the conflict could be erased, and the basis of the future organization of the country could remain.

After the complete liberation of the Italian Peninsula from German and fascist occupation and after the end of the conflict, new political orientations strongly emerged.

After Ivanoe Bonomi, the government was still formed by representatives of all (or almost all) the antifascist parties, but it was a weak government, victim of the growing confrontation between left-winged parties and the moderate powers, which were influenced by the Vatican and Anglo-American representatives, who put on pressure in order to guide the political Italian future against communism. The experience of Ferruccio Parri’s government, ancient leader of the Italian Resistenza, was emblematic.

Even though they weren’t sure about the success of a referendum in a country that not long ago was dominated by fascism, that had also enjoyed from the Italians’ consent, the parties that supported republic accepted the introduction of the referendum in order to avoid the indefinitely postponement of elections.

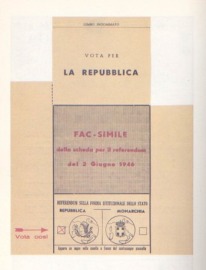

The Communist Party, the Socialist Party and the Action Party requested that elections for the Constituent Assembly and the referendum would take place the same day. The Legislative Decree of the Lieutenant of the Realm no. 98 of 16th March 1946, started by the government of the Christian democrat Alcide de Gasperi, guaranteed the decision of putting the election between monarchy and republic to a referendum. So, the Legislative Decree no. 99 of 16th March 1946 proclaimed the referendum and Constituent Assembly’s elections for 2nd June 1946.

The Communist Party, the Socialist Party, the Action Party and the Republican Party openly declared themselves republicans. Republic was also supported by some liberal representatives and almost all the leaders of the Christian Democracy Party, but their position wasn’t shown for a long time since most of Catholic electors had a close attitude towards monarchy. They decided to relate the institutional fate of Italy to Catholic religion. Church was first interested in protecting the moral and the returning of the values of Christian life, in which Italians were recognised because of their culture, tradition and character. Although this party openly showed a neutral position on the institutional issue, it actually acted in favour of monarchy.

Monarchy supporters trusted the Savoy House, as they could guarantee the Catholic cultural roots of Italy and the national unity conquered by the Resurgence, a unit that should be safeguarded against the many social, economic and cultural differences of the Italian territory.

It was very clear that the ones who considered themselves in favour of monarchy controlled all the renovation projects that socialist and communists wanted to develop. Leaflets for monarchy demonstrated the danger that social changes could cause: a social-communist dictatorship, the destruction of social and public order and a civil war.

For the other hand, republic supporters highlighted the mistakes of the Savoy House from the moment they affirmed fascism power: having given the government to Mussolini in 1922, having approved the coming back to dictatorship in 1925 after the murder of socialist Giacomo Matteotti (ordered by the Duce), having supported fascist colonialism and war in the Nazi’s side, the defeat of Italian army when it was abandoned without orders on 8th September 1943 and their betrayal when they run away from Rome, an act that allowed the military occupation by Germany and many terrible consequences for the Italian people. The republican choice should have prevented Italy from falling again into the past, it should have fought the risks that allowed the coming to power of a dictator.

The combination of referendum and elections for the Constituent Assembly put the electoral campaign on top of the referendum about monarchy, and it seemed that the first one prevailed over the second one because, for the one hand, the parties for republic needed to distinguish between themselves in the electoral programs before elections. For the other hand, during the campaign for 2nd June divisions between moderates and conservatives (headed by the Christian Democracy Party) and left-winged progressives started to show.

Victor Emanuel III, in his last attempt of saving the Savoy dynasty and the monarchy, not respecting the ‘institutional truce’, abdicated the throne in his son a few weeks before elections. His son, who was Lieutenant General of the Realm, became King Humbert II. The success of the referendum ended with the victory of the republic and the exile of the new king and his family.

Republic wasn’t supported by a large majority. Southern and center Italy expressed their wishes for monarchy. Due to the short time in which the country passed from Nazi occupation to liberation thanks to Anglo-American allies, in the south of the country the Partisan Movement didn’t develop as much as in the north, despite the presence of armed opposition against the Germans, like the episodes that took place in Naples and Campania. This is the reason why southern Italians weren’t that familiarised with Resistenza movements.

To all this we have to add the traditional and symbolic feeling of monarchy, which was also strengthen by the Allies, who used it as a transition route to postfascism and social order maintenance. We shouldn’t forget that monarchy also received the support of the political movement Front of the Ordinary Man, which was very conservative and extended in the south and between mafias. There were exceptions in some southern areas between 1943 and 1946, where farmers, tired of working in landowners’ lands in very poor conditions, voted for republic. In some areas in northern Italy there were high percentages for monarchy, where the tradition of the Savoy was very strong. The fear to change and the uncertain future that republic carried itself were the reasons why monarchy didn’t win by few votes. This vote for monarchy was specially expressed by some public sectors, professional fields, landowners and Catholics who followed Vatican’s demands. In other words, by those who feared that rupture with ancient traditions could give way to a loss in social status and values.

However, the republic, headed by left-winged parties, received the favour of those who condemned fascism and the monarchy that had supported it, and who expected a radical overcoming of the past. Regarding this, the republican choice was due to the Resistenza period, the breaking-off with the past and the change that led to the Italian outlook.

Republic’s victory wasn’t a deep change backed by its supporters. Actually, there were many continuity routes which gathered the experience of the different aspects of Italy: republican, liberal and fascist, even though the results of Resistenza and the referendum and the most advanced aspects of the Constitution, in force from 1948.

While there were still some unsolved problems from the fascist past, national and international political contrasts and the growing contrast between the western and the eastern blocks determined a moderate change, in comparison with expectations that rose during the Partisan Movement; a change that should have marked the Italian political life for the next decades.

Pingback: Doing away with monarchy - Page 19 - Historum - History Forums

Pingback: A look under the world’s hood: Italy | A Yankee War Bride in the Midwest

Pingback: The Fall of the Italian Monarchy – Social Change Blog